Rare books

MIT’s Department of Distinctive Collections is home to thousands of rare books and manuscripts with an expansive range. Many texts represent foundational and fundamental scientific discovery and achievement. Works by prominent figures such as Georgius Agricola, Robert Boyle, Marie Curie, Michael Faraday, Otto von Guericke, Caroline Herschel, Ada Lovelace, Isaac Newton, Mary Somerville, Alessandro Volta are included, as are less universally recognizable scientists.

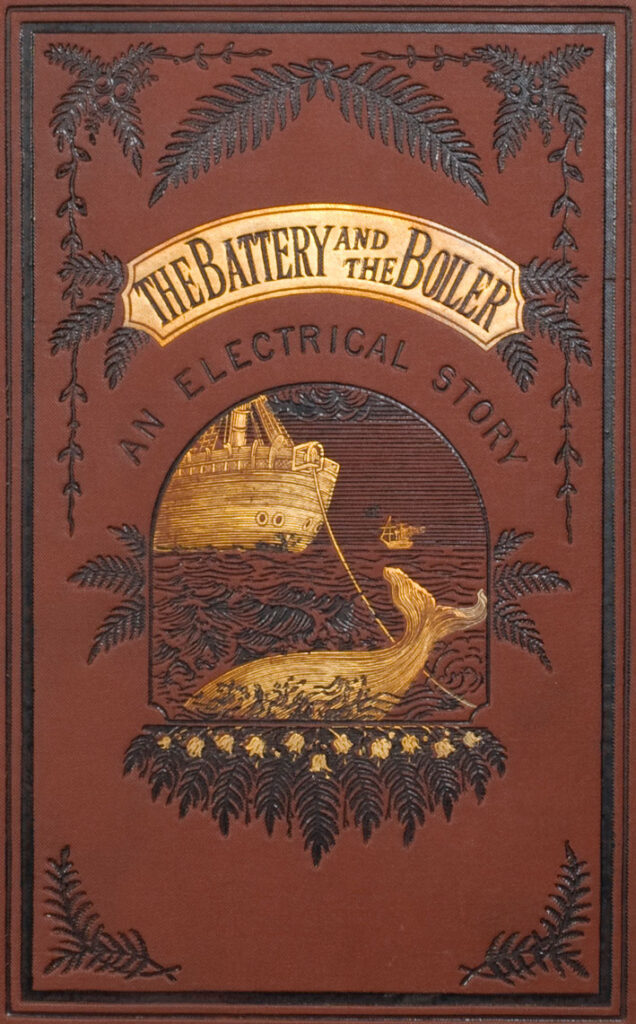

The Battery and the Boiler: An Electrical Story. Distinctive Collections, MIT Libraries.

Topically, the collection is rich in materials on

- electricity, electrical engineering, magnetism (including animal magnetism),

- lighter-than-air travel, telegraphy, and popular science.

It delves into some perhaps unexpected areas as well, covering such topics as

- witchcraft and mesmerism,

- horology (study and measurement of time)

- gymnastics and exercise

- politics, poetry, and even dentistry

Some collection highlights include:

- Book of Hours a French manuscript, lavishly illuminated, from the early 15th-century

- Book of Hours printed on vellum a curiously elaborate example, from the early 16th-century

The collection also includes obscure incunables – books printed before 1501 – like Coniuratio Malignorum Spirituum, a handbook on exorcisms, as well as some of the best documented and most recognized texts of the Middle Ages, like the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle.