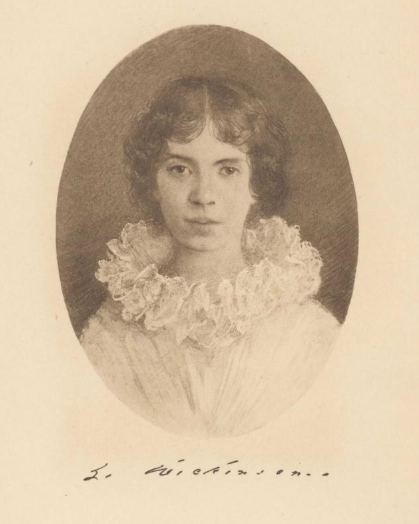

Martha Dickinson Bianchi wrote of her aunt, Emily Dickinson, “She was not daily bread. She was star dust.” Bianchi’s The Life and Letters of Emily Dickinson, the 1924 book which MIT Libraries has scanned and made available to all in celebration of Public Domain Day 2020, is neither an accurate account of the poet’s life nor a personal memoir from a family member. This is evident in the photogravure (basically a retouched photograph) of Dickinson by artist Laura Coombs Hill that opens the book. It’s a version of the one known photograph, which she and her sister never liked, to which curls, softer features, and a frilly dress have been added. It was commissioned after the poet’s death, and in the book Bianchi admits it may not look much like Dickinson. This isn’t a book about how Dickinson was, though; it’s about how her family saw her, and how they want her to be remembered.

Martha Dickinson Bianchi wrote of her aunt, Emily Dickinson, “She was not daily bread. She was star dust.” Bianchi’s The Life and Letters of Emily Dickinson, the 1924 book which MIT Libraries has scanned and made available to all in celebration of Public Domain Day 2020, is neither an accurate account of the poet’s life nor a personal memoir from a family member. This is evident in the photogravure (basically a retouched photograph) of Dickinson by artist Laura Coombs Hill that opens the book. It’s a version of the one known photograph, which she and her sister never liked, to which curls, softer features, and a frilly dress have been added. It was commissioned after the poet’s death, and in the book Bianchi admits it may not look much like Dickinson. This isn’t a book about how Dickinson was, though; it’s about how her family saw her, and how they want her to be remembered.

Bianchi, herself an author and poet, describes her aunt and the community around them from her perspective. She calls one friend “a gay madcap of a girl” (p. 76), but spends much of the book insisting that her aunt was “perfectly normal” (p. 20) and “perfectly natural, too” (ibid). She replaces the popular image of Dickinson as a death-obsessed reclusive spinster in white with a warm, loving woman who had deep relationships and just happened to really, really like being home. While she glosses over some suspected romantic dalliances, she describes Dickinson’s relationship with a young law student as “a spicy affair.” Maybe this meant something different in 1924?

Be prepared to get curious when reading this book. I found myself searching for more information about almost every relationship described. Wait, this Otis Lord who’s described as a dear friend — wasn’t he the best friend of her father she allegedly was caught canoodling and considered marrying? This beloved sister in law…aren’t those letters kind of romantic? Did Emily just refer to herself using male pronouns? The Life and Letters of Emily Dickinson is a fantastic way to rekindle your relationship with Emily Dickinson, while enjoying the familial, 1920s lens through which her niece creates her narrative. Bianchi may not be the final word on her aunt’s flesh and soul, but we can all agree on the fire of her imagination: “She had the soul of a monk of the Middle Ages bound up in the flesh of Puritan descent, and, from Heaven only knows where, all the fiery quality of imagination for which genius has been burned at the stake in one form or another since the beginning” (p. 95).

This post was written for Public Domain Day 2020 by Jen Greenleaf, Librarian for Women and Gender Studies