Wigmaking

The volumes of plates open in the floor cases and wall cases of the gallery displayed single plates of great interest for understanding the treatment of the mechanical arts in the Encyclopédie. Each of these images was one part of a series of plates devoted to a single manufacturing process (printing, cork-making, dying, etc.) from start to finish, as a way to make useful information available to the public. On the window wall we reproduced twelve plates devoted to a single trade, in this case wig-making and hair care, an important personal appearance trade in eighteenth-century France.

Both men and women of means in France wore wigs during this period. While the elaborately sculpted, impossibly tall, female wigs associated with Marie-Antoinette and the court of Louis XVI have become a cliché of the aristocratic excesses that spawned the French Revolution, many contemporaries accepted that it was part of their public persona to wear a more modest hairpiece when at work or in society. To obtain suitable hairpieces, they went to the shops of master wigmakers where they were fitted for the latest designs.

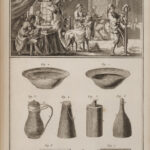

The wigmaking plates reproduced in the exhibit demonstrated many of the visual formulae employed by the artists and engravers who supplied the plates for the Encyclopédie. The top half of the first image (Plate I) represents a wigmaker-barber’s shop, where we see employees working at a number of tasks related to wigmaking and barbering, including a barber shaving a customer (a); others creating tresses of hair and fastening them to wigs (b,c,d); and a boy who stokes a fire used to heat irons for curling hair (e).

The wigmaking plates reproduced in the exhibit demonstrated many of the visual formulae employed by the artists and engravers who supplied the plates for the Encyclopédie. The top half of the first image (Plate I) represents a wigmaker-barber’s shop, where we see employees working at a number of tasks related to wigmaking and barbering, including a barber shaving a customer (a); others creating tresses of hair and fastening them to wigs (b,c,d); and a boy who stokes a fire used to heat irons for curling hair (e).

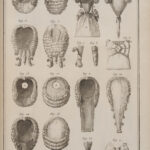

In the bottom half of this first plate and in subsequent plates, Diderot and his artistic collaborators represent the many tools, molds and techniques employed in the complex process of producing fashionable hairpieces. Note in particular the instruments for measuring heads and wigs in Plate III; wig patterns and tools used by wigmakers in Plates V and VI; and common examples of wigs and the queues affixed to them in Plates VII and VIII.

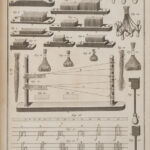

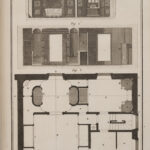

Finally, in the last four plates, we see details of public baths situated along the Seine River in Paris. From our 21st-century perspective, it is difficult to imagine what public baths had to do with wigmaking, particularly because most of us are not today consumers of either product. But in pre-revolutionary France, almost all economic activity was regulated by royally-chartered guilds. By the early eighteenth-century, it was customary throughout the kingdom to group wigmakers, barbers, and public bath providers in the same guildhall. A 1718 Parisian guild statute makes the connections between these three activities explicit: “To the barbers, wigmakers, and water and steam bath providers alone belongs the right to shave and style facial hair, to give baths, to make wigs, to offer steam baths, & to create all other sorts of hair products, as much for men as for women….”

It was this world of strictly regulated economic activity, with its carefully guarded trade secrets, that Diderot and his team of writers and engravers set out to explore, and perhaps reform, in the pages of the Encyclopédie.

Plates:

See also: Wigmaking Plates with Descriptions (PDF)