The 1880s witnessed a surge of pivotal and enduring electrical innovations: domestic-use light bulbs, alternating current motors and transformers, power stations, hydroelectricity, electric elevators, streetcars, dishwashers, and ovens. By decade’s end, plenty of electrical appliances for the home existed. However, due to a variety of factors—most of all a lack of uniform power distribution in Europe and the U.S. (see 1885’s entry on the Schuyler Electric Light Company)—such things remained, for the time being, the domain of the academy and the rich.

L’électricité a la Maison was out to change that. Neither a cash-in on the electricity “craze” nor an advertisement passing for a handbook, L’électricité is an instructional manual/inspirational sourcebook that appealed to tinkerers who, motivated by electricity’s timesaving promises and a little bit of romance, were tired of waiting for prices to drop and power systems to expand. Recent innovations such as the electric tricycle and the electric horse bridle are deconstructed piece by piece, their mechanisms succinctly explained. Readers are assured they can indeed try this at home.

L’électricité a la Maison was out to change that. Neither a cash-in on the electricity “craze” nor an advertisement passing for a handbook, L’électricité is an instructional manual/inspirational sourcebook that appealed to tinkerers who, motivated by electricity’s timesaving promises and a little bit of romance, were tired of waiting for prices to drop and power systems to expand. Recent innovations such as the electric tricycle and the electric horse bridle are deconstructed piece by piece, their mechanisms succinctly explained. Readers are assured they can indeed try this at home.

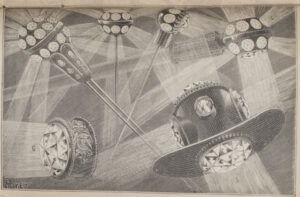

Though L’électricité is based on the demystification of newfangled electric devices, it is far from cynical. The charm of the book comes from the  sheer breadth of items described, from the mundane to the truly bizarre. Alarms, doorbells, batteries, telephones, sirens—yes, they’re all here. But were you considering a monorail for your home? How about lights for your carriage driver’s hat? Illuminated jewels for your tiara? An illuminated rifle barrel to more accurately target your prey? A death’s head hatpin with illuminated eyes? It’s all in the book, explained with startling objectivity and directness. Alternately mundane and staggering to modern eyes, L’électricité offers the amateur electrician instructions that are simultaneously pragmatic about decoding electricity’s mysteries and giddy about the endless possibilities of an electrified future.

sheer breadth of items described, from the mundane to the truly bizarre. Alarms, doorbells, batteries, telephones, sirens—yes, they’re all here. But were you considering a monorail for your home? How about lights for your carriage driver’s hat? Illuminated jewels for your tiara? An illuminated rifle barrel to more accurately target your prey? A death’s head hatpin with illuminated eyes? It’s all in the book, explained with startling objectivity and directness. Alternately mundane and staggering to modern eyes, L’électricité offers the amateur electrician instructions that are simultaneously pragmatic about decoding electricity’s mysteries and giddy about the endless possibilities of an electrified future.