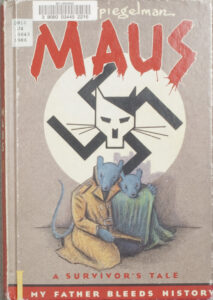

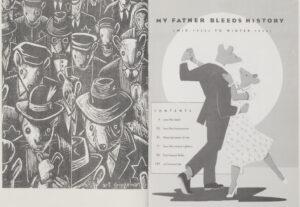

Art Spiegelman’s Maus was originally published in serial form beginning in 1980, in the comic anthology Raw. It appeared in book form in 1986, when volume I, “My Father Bleeds History,” was published by Pantheon Books. More than thirty years after its initial appearance, Maus hasn’t lost an ounce of its narrative power. Nor has it lost its power to surprise.

Spiegelman’s fusion of illustration, biography, history, and personal tragedy continues to confound expectations. Maus may be the most unlikely artistic triumph of the 20th century.

In theory it just shouldn’t work. On first hearing, in fact, the concept seems impossible to pull off without giving serious offense. It’s the true story of Spiegelman’s parents – Polish Jews, survivors of the Holocaust – told in cartoon form, with the Jews portrayed as mice, the Nazis as cats. The modern-day relationship between Spiegelman and his father frames the narrative.

The book is about several important things: death, hatred, and the Holocaust; the immigrant experience in America; elderly couples with marriage troubles; the relationship between immigrant parents and their completely Americanized adult children.

The book is about several important things: death, hatred, and the Holocaust; the immigrant experience in America; elderly couples with marriage troubles; the relationship between immigrant parents and their completely Americanized adult children.

It’s also about what people choose to remember and what they try to forget. Or perhaps more accurately, it’s about whether people are willing to share those things that are painful to remember, even if those painful things have made them who they are.

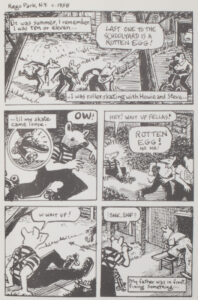

Spiegelman’s approach is actually brilliant: readers are disarmed by the cartoon format, and find themselves drawn into a story they might otherwise be reluctant to approach. The Holocaust sections are grueling. But even the framing device, set in the present day, is filled with painful encounters as the narrator – Spiegelman himself, drawn as a mouse – attempts to connect with an elderly father who is bitter, depressed and emotionally withdrawn.

As improbable as it seems, this book ends up  working not in spite of its central conceit, but precisely because of it. The overall effect is profound and at times shattering.

working not in spite of its central conceit, but precisely because of it. The overall effect is profound and at times shattering.

Certain theater pieces are revelatory in live performance. But when they’re committed to film, no matter how skilled the filmmaker, all immediacy is somehow drained, the drama is gone, and the piece lies there, inert: it turns out that it wasn’t just “the story” that was magic, but the manner of telling it. Maus is similar in a certain sense. The work is completely sui generis. The story of Vladek and Anja and of their son Art, the story of the horrors they witnessed, and the story of the lives they experienced in different times and places, can only be conveyed with this much impact if it’s told in this one specific way.

Maus cleared a path for other nonfiction graphic narratives that would also dwell on very serious topics. Some of them are extremely powerful: Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis concerns the Iranian revolution of the 1970s as it was experienced at ground level. Stan Mack’s Janet & Me traces the illness and death of Mack’s wife from cancer. There are others. But there wouldn’t be, if Maus hadn’t come first.

Maus cleared a path for other nonfiction graphic narratives that would also dwell on very serious topics. Some of them are extremely powerful: Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis concerns the Iranian revolution of the 1970s as it was experienced at ground level. Stan Mack’s Janet & Me traces the illness and death of Mack’s wife from cancer. There are others. But there wouldn’t be, if Maus hadn’t come first.

Unsurprisingly, when Maus won the Pulitzer Prize, it flummoxed the Pulitzer Prize Board, who found it to be unclassifiable. Their only option was to grant it a prize in the “Special Awards and Citations” category.