The tank. The U-boat. The fighter plane. The machine gun. The flamethrower. Poison gas. These military technologies were all developed or enhanced during World War I, the first time science, technology, and mass production played a critical role in the course of a war. These technologies also played a critical role in the war’s unprecedented carnage. Defined by destructiveness, scale, and technical innovation, World War I is seen as a watershed, the advent of the modern age.

With our knowledge of the part “war inventions” played in the First World War’s horrors, today it seems a bit incongruous that this was considered a fitting subject for the fourth installment of the “Science for Children Library” as the war raged on in 1917. (MIT’s copy is a 1919 reissue.) But as Gibson affirms in the preface, “It goes without saying that the subject of War Inventions was suggested by the Great European War. During these years of warfare even children became interested in the instruments of destruction used in that barbarous thing which we call War.”

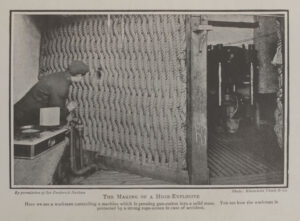

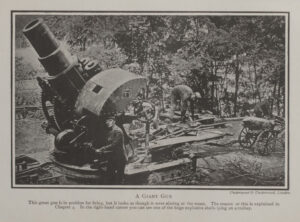

Gibson covers the development of guns from early canons to “guns that fire one thousand shots per minute,” ships from ironclads to submarines, explosive weapons from the first shells to torpedoes and mines, and flying machines from zeppelins to “aeroplanes.” (There is no mention of poison gas even though World War I is often called the “chemists’ war.”)

Gibson covers the development of guns from early canons to “guns that fire one thousand shots per minute,” ships from ironclads to submarines, explosive weapons from the first shells to torpedoes and mines, and flying machines from zeppelins to “aeroplanes.” (There is no mention of poison gas even though World War I is often called the “chemists’ war.”)

After 250 pages of genial but detached instructive prose, Gibson heads into moral terrain for a few closing paragraphs. He writes, “the conclusion of the whole matter is that with the dreadful experience of the Great War all nations may agree to combine together in a  real endeavour to make further wars impossible.” As for what had already transpired? In response to the “worthless” arguments of pacifists, conscientious objectors, and people who “say we had no right to make such machines of war,” he says “we are confident that our children’s children will agree that we did the right thing in taking part in the Great War.”

real endeavour to make further wars impossible.” As for what had already transpired? In response to the “worthless” arguments of pacifists, conscientious objectors, and people who “say we had no right to make such machines of war,” he says “we are confident that our children’s children will agree that we did the right thing in taking part in the Great War.”