The automobile, the machine that so profoundly shapes our culture, economy, politics, and environment, appeared in its earliest guise in France in 1760 as an artillery-hauling, steam-powered three-wheeler. Invented by army officer Nicholas Cugnot, the ungainly tricycle’s career was cut short by a crash. In the 19th century, a variety of vehicles powered by both steam and electricity proliferated. The gasoline-burning internal combustion engine, the automotive technology that (as we all know) would ultimately prevail over steam and electricity, was invented independently by Germans Karl Benz and Gottlieb Daimler in the 1880s.

By the end of the 19th century, France was the center of the automobile’s technical development and production, but American demand for autos surged by the turn of the century, and the U.S. became the focal point for automobile manufacture. You have probably already guessed, dear reader, the next several key words in early automobile history: Henry Ford, mass production, 1908, Model T. Ford understood the extent of the U.S. market for a basic, affordably priced car, and the automobile soon became a fundamental feature of American life.

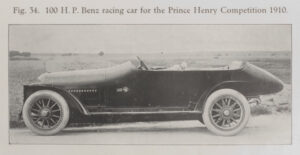

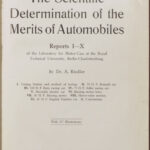

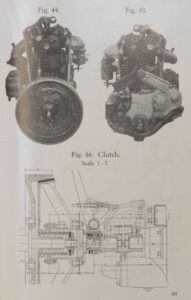

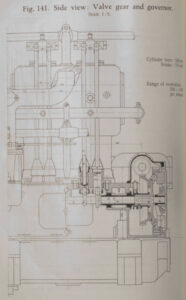

This book’s author, Austrian mechanical engineer Alois Riedler, established the Laboratory for Internal Combustion Engines at the Royal Technical University, Berlin-Charlottenburg in 1903 and began investigations of motor vehicles in 1907. This volume is Riedler’s condensation and translation of a set of ten reports originally published in German. The reports show the results of investigations into Renault, Benz, and Adler racing cars, a “Mercédès electromobile,” military transports, and an English Daimler-Knight car.

Riedler writes that the “end in view” of his work “is an ambitious one: the purely objective valuation of all the important features of the motor vehicle, free from subjective, casual and impermissible influences.” He bemoans the “subjective method of valuation” drawn from racing results that automobile manufacturers used (along with advertisements) to boost their cars’ reputations. In the absence of reliable, honest means to measure cars’ performance, automobile “development has been enormously influenced even by mere caprices of fashion” and “large sums are expended, regardless of the real value of the innovation.” Moreover, “reliable, comprehensive and at the same time complete statistics are not obtainable from [automobile] makers” because of the companies’ need for secrecy from competitors.

Riedler writes that the “end in view” of his work “is an ambitious one: the purely objective valuation of all the important features of the motor vehicle, free from subjective, casual and impermissible influences.” He bemoans the “subjective method of valuation” drawn from racing results that automobile manufacturers used (along with advertisements) to boost their cars’ reputations. In the absence of reliable, honest means to measure cars’ performance, automobile “development has been enormously influenced even by mere caprices of fashion” and “large sums are expended, regardless of the real value of the innovation.” Moreover, “reliable, comprehensive and at the same time complete statistics are not obtainable from [automobile] makers” because of the companies’ need for secrecy from competitors.

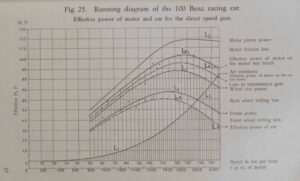

Riedler appears in this book as a pioneer in automotive engineering, having over the course of years developed “test stands and measuring instruments” for experiments on cars. In addition to measurements on the test stand, he and his colleagues completed 30,000-mile long-distance trials and gathered statistics based on annual road-testing of all “public vehicles.” Riedler states that “each investigation yields surprising information and reveals contradictions of the untenable views which have prevailed,” and his work points to possible paths of technological progress.

As it happens, Riedler is also the inventor of the pump valve mechanism in the Leavitt-Riedler Pumping Engine, designed by Cambridge, Massachusetts engineer Erasmus Darwin Leavitt, Jr. and installed in 1894 at the Chestnut Hill Pumping Station on Beacon Street near Cleveland Circle. The engine has been declared a landmark by ASME, the American Society of Mechanical Engineers.