No other consideration – and certainly no other commodity – has as much influence on American foreign policy as oil. In the second decade of the 21st century, the United States is completely dependent on a vast and steady supply of petroleum products in order for it to function in any familiar way.

On the political front, voices from all sides lament the nation’s lack of alternatives to “foreign oil.” Breaking free of our dependency on a finite substance that comes largely from a volatile part of the world is a goal most Americans profess to share. But the political reality is that there are huge obstacles to changing the way we live and do business. People want cheap, plentiful gas to fuel their cars. There’s clear resistance to a carbon tax. Oil companies are massively huge players in American politics. Our relationships with oil-producing countries are tentative at best. And none of this is new.

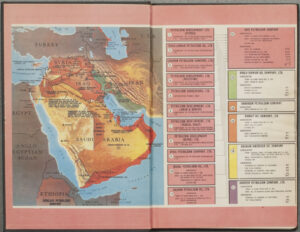

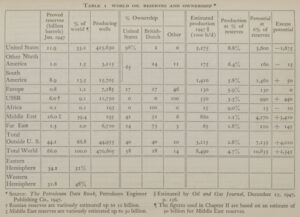

Arabian Oil, published by the University of North Carolina Press in 1949, provides a look back at a problem which has changed surprisingly little during the 60-plus years since the book’s publication. The authors’ main focus is on economics and business: they tell us what’s involved in the extraction and marketing of oil from Middle Eastern nations. But they also voice a concern that’s echoed by political observers in the present day: American dollars spent on petroleum products may prop up governments, or perpetuate dynasties, of questionable merit.

Arabian Oil, published by the University of North Carolina Press in 1949, provides a look back at a problem which has changed surprisingly little during the 60-plus years since the book’s publication. The authors’ main focus is on economics and business: they tell us what’s involved in the extraction and marketing of oil from Middle Eastern nations. But they also voice a concern that’s echoed by political observers in the present day: American dollars spent on petroleum products may prop up governments, or perpetuate dynasties, of questionable merit.

American companies pay millions of dollars directly to the rulers of oil-rich countries for the right to run their oil operations. A portion of that income, Mikesell and Chenery tell us, is then distributed to tribes or factions within the country’s population.

Since there is little distinction between the revenues of the monarch and those of the state which he governs, the payments appear as the largess of a benevolent tribal leader to his less opulent followers.

Perhaps the most fascinating single aspect of the volume appears at its end. Chapter 8 is entitled “Prospects and Conclusions,” and was clearly intended to close the book. But there’s an appended Chapter 9 – “Some Recent Developments” – that begins:

Since February 1948 when the foregoing chapters were completed, political and economic events affecting the future of Arabian oil have moved rapidly. The serious political disturbances in the Middle East have interfered with both current operations and planning for the future.

The political situation in the Middle East had been volatile since before World War I, but by 1949 it was becoming explosive. It’s doubtful that this book’s authors could have guessed that issues that were just then beginning to emerge would still be reverberating across the globe more than sixty years later. This scholarly text focuses largely on the  economics of oil, but also urges the United States to devise a sane and workable “foreign petroleum policy.” In the book’s tacked-on final chapter, the authors register dismay at the rapidity with which seemingly unbreakable, long-term international agreements could be dissolved, and various economies thrown into turmoil. It’s an alarm that continues to echo in today’s headlines.

economics of oil, but also urges the United States to devise a sane and workable “foreign petroleum policy.” In the book’s tacked-on final chapter, the authors register dismay at the rapidity with which seemingly unbreakable, long-term international agreements could be dissolved, and various economies thrown into turmoil. It’s an alarm that continues to echo in today’s headlines.