Published: Boston, 1995

Spring moves over the temperate lands of our Northern Hemisphere in a tide of new life, of pushing green shoots and unfolding buds … the different sound of the wind which stirs the young leaves where a month ago it rattled the bare branches. These things we associate with the land, and it is easy to suppose that at sea there could be no such feeling of advancing spring. But the signs are there, and seen with the understanding eye, they bring the same magical sense of awakening.

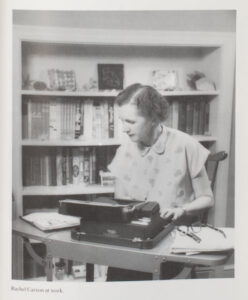

In The Sea Around Us, Rachel Carson drew on her professional experience as  a marine biologist to write about oceanography for a general readership. Her science was solid, but her engaging style was also imbued with a poetic “sense of wonder” (a theme to which she often returned). The book was a bestseller when it was published in 1951, and the royalties it generated brought her financial independence and allowed her to realize her dream of building a summer cottage in Maine. At home in Maryland she lived with and cared for her elderly mother, and supported an ailing niece and grandnephew. In her visits to Maine, she could devote herself fully to her writing in the coastal surroundings she dearly loved.

a marine biologist to write about oceanography for a general readership. Her science was solid, but her engaging style was also imbued with a poetic “sense of wonder” (a theme to which she often returned). The book was a bestseller when it was published in 1951, and the royalties it generated brought her financial independence and allowed her to realize her dream of building a summer cottage in Maine. At home in Maryland she lived with and cared for her elderly mother, and supported an ailing niece and grandnephew. In her visits to Maine, she could devote herself fully to her writing in the coastal surroundings she dearly loved.

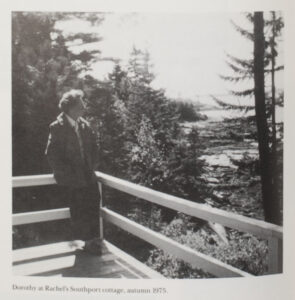

While overseeing the cottage’s construction on Southport Island in 1953, Carson met summer residents Dorothy and Stanley Freeman. Dorothy had read and admired The Sea Around Us, and had written to Rachel in the fall of 1952 to welcome her as a new neighbor. During their brief time together that first summer, Rachel and Dorothy formed an immediate friendship as they explored the marine life of the local tide pools. Their bond deepened in intimacy and affection through the letters they wrote upon returning home, Dorothy to Massachusetts, and Rachel to Maryland.

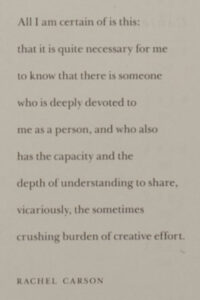

Their correspondence continued through the years during the fall, winter, and spring months that they spent away from each other. For both Rachel and Dorothy, their relationship filled a need that no one else could. If the basis of their friendship lay in their shared “sense of wonder” at the natural world around them, in their letters what is most evident – and most moving – is their unceasing sense of wonder at having found one another. Always, Rachel is a beautifully compiled volume of their 12-year correspondence.

Their correspondence continued through the years during the fall, winter, and spring months that they spent away from each other. For both Rachel and Dorothy, their relationship filled a need that no one else could. If the basis of their friendship lay in their shared “sense of wonder” at the natural world around them, in their letters what is most evident – and most moving – is their unceasing sense of wonder at having found one another. Always, Rachel is a beautifully compiled volume of their 12-year correspondence.

It was during these years that Rachel Carson wrote her seminal work, Silent Spring.

She did not lightly take on the task of researching and documenting the destructive effects of DDT and other chemicals, but she felt she had to. A clarion call to the dangers of the reckless use of herbicides and pesticides, Silent Spring caused an uproar after the first of three installments appeared in the June 15, 1962 issue of The New Yorker.

The personal attacks from the chemical industry were even more vicious than Carson anticipated, but the ensuing publicity ultimately helped her cause. And her science was solid: the report of an advisory panel – established by MIT’s Jerome Wiesner, science advisor to President Kennedy – supported her findings, with the recommendation that “elimination of pesticides should be a goal” (though Carson herself called only for  regulation and ecological balance, not a total ban).

regulation and ecological balance, not a total ban).

By the time Silent Spring was published, Carson knew it would be her last book. Since 1958, she had been struggling with cancer, arthritis, and heart disease. She lived to see the initial impact of her work, and found satisfaction in achieving what she’d set out to do. But since then it has become clear: Silent Spring laid the foundation for a new ecological consciousness – it changed the world. Rachel Carson died at age 56 on April 14, 1964.

Always, Rachel ends with the last letters Dorothy would receive from Rachel. Written in January and April of 1963, Rachel left them to be delivered to Dorothy posthumously.

In her January 24 letter, she wrote:

Darling [Dorothy],

I have been coming to the realization that suddenly there might be no chance to speak to you again and it seems I must leave a word of goodbye …

When I think back to the many farewells that have marked the decade (almost) of our friendship, I realize they have almost been inarticulate. I remember chiefly the great welling up of thoughts that somehow didn’t get put into words – the silences heavy with things unsaid. But then we knew or hoped there was always to be another chance – and always the letters to fill the gaps …

What I want to write of is the joy and fun and gladness we have shared – for these are the things I want you to remember – I want to live on in your memories of happiness. I shall write more of those things. But tonight I’m weary and must put out the light. Meanwhile, there is this word – and my love that will always live.

And on April 30, 1963:

My darling, You are starting on your way to me in the morning, but I have such a strange feeling that I may not be here when you come – so this is just an extra little note of farewell, should that happen. There have been many pains (heart) in the past few days, and I’m weary in every bone. And tonight there is something strange about my vision, which may mean nothing. But of course I thought, what if I can’t write – can’t see to write – tomorrow? So, a word before I turn out the light…

And her closing words:

Darling – if the heart does take me off suddenly, just know how much easier it would be for me that way. But I do grieve to leave my dear ones. As for me, however, it is quite all right. Not long ago I sat late in my study and played Beethoven, and achieved a feeling of real peace and even happiness.

Never forget, dear one, how deeply I have loved you all these years.

Rachel