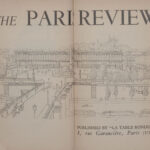

Published: Paris and New York, 1953

The Paris Review is justly famous for its impressive list of founding editors and advisors (George Plimpton, Peter Matthiessen, Donald Hall, Archibald MacLeish, et al.) as well as for the galaxy of writers whose work has appeared in its pages. In its first year alone, the journal featured material by Adrienne Rich, Donald Windham, Richard Wilbur, Simone Weil, Terry Southern, and other luminaries. During its second year, the Review would publish one of the first works in English by Samuel Beckett.

The editors opened their series on “The Art of Fiction” in their very first issue with a bang: an interview with E.M. Forster, who at the time was the foremost living British man of letters. By 1953, nearly 30 years had elapsed since Forster had published his fifth novel, and he’d long since announced that there would be no others during his lifetime.

His reputation had risen and fallen and risen again. Forster was no literary modernist; indeed in this  issue of The Paris Review he acknowledges his debt to Jane Austen. But he was a modern man. He understood that class distinctions could be nuanced to the point of near-invisibility, yet still get in the way of the most important thing in the world: honest human interaction. Forster managed to shed light on the most microscopic of human differences through writing of remarkable subtlety and grace. But for all his quiet gentleness, Forster abhorred ugliness and cruelty, and when tackling the issues of class and race he wrote with firmness and with his sense of outrage in full view.

issue of The Paris Review he acknowledges his debt to Jane Austen. But he was a modern man. He understood that class distinctions could be nuanced to the point of near-invisibility, yet still get in the way of the most important thing in the world: honest human interaction. Forster managed to shed light on the most microscopic of human differences through writing of remarkable subtlety and grace. But for all his quiet gentleness, Forster abhorred ugliness and cruelty, and when tackling the issues of class and race he wrote with firmness and with his sense of outrage in full view.

Though Forster’s novels may not be modern in any experimental, boundary-pushing sense, they do convey the modernist’s refusal to be told how to act or what to feel. And though his voice may be muted, it’s stubbornly insistent. The author is passionate about seemingly small things, chief among them that most quiet of virtues, simple decency. He celebrates people who are kind even when it’s inconvenient, who are generous when it’s at all possible, and who are conscious always of the individual rather than the group. It sounds simple, but in practice it can be revolutionary.

In this first issue of the Review, the normally self-effacing Forster makes a somewhat surprising admission regarding his own writing:

Of course I like reading my own work, and often do it. I go gently over the bits that I think are bad … I have always found writing pleasant, and don’t understand what people mean by “throes of creation.” I’ve enjoyed [the act of writing, and] believe that in some ways [my work] is good. Whether it will last, I have no idea.

The question of whether E.M. Forster’s work will last has been settled for some time now. Of the five novels published while he lived, at least four are close to perfect, and one of them – A Passage to India – is as important as any novel published during the 20th century.