“A work of art, be it never so humble, is long-lived; we never tire of it; as long as a scrap hangs together it is valuable and instructive to each new generation. All works of art have the property of becoming venerable amidst decay.” – William Morris, Art and Socialism, p. 17.

If one were to settle on a principal theme of the work of William Morris, it would very likely be permanence and, more specifically, the predominance of durability over ephemerality. Morris’ many writings on art, often published by his own Kelmscott Press, promote the inherent integrity of handcraft over machine production and elucidate the indelible bond between craftsman and user. Heir to Gothic Revivalists A.W.N. Pugin and John Ruskin, as well as social critics Henry David Thoreau and Thomas Carlyle, he was prescient in championing simple, durable, handmade home furnishings – textiles, wallpaper, furniture – in the face of the ostentatious Victorian design status quo and the concurrent rise of mass-produced consumer goods. Though the march of industrialized mass production would prove unyielding, Morris’ own production was an argument for the necessity of art in every person’s daily life.

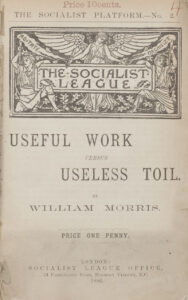

Not simply an artisan, Morris was a painter, a poet, an  architect, an entrepreneur, and, especially later in life, a political firebrand. His beliefs paralleled those of the infamous Luddites (British textile artisans of a generation before Morris who protested the dehumanizing production methods brought forth by the Industrial Revolution), but Morris was anything but politically conservative. He was a member of Britain’s first socialist organization, the Democratic Federation, and later, with Karl Marx’s youngest daughter Eleanor, formed the Socialist League, a workers’ advocacy group.

architect, an entrepreneur, and, especially later in life, a political firebrand. His beliefs paralleled those of the infamous Luddites (British textile artisans of a generation before Morris who protested the dehumanizing production methods brought forth by the Industrial Revolution), but Morris was anything but politically conservative. He was a member of Britain’s first socialist organization, the Democratic Federation, and later, with Karl Marx’s youngest daughter Eleanor, formed the Socialist League, a workers’ advocacy group.

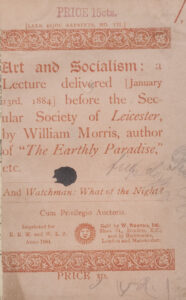

Not averse to lecturing on street corners despite a London ban on public Socialist oration, Morris, inspired by a recent reading of the French translation of Marx’s Das Kapital (an English translation was not published until 1886), delivered a more intimate lecture to the Secular Society of Leicester on January 23, 1884. It was soon published as a pocketbook manifesto entitled Art and Socialism. A very reasonable defense of the sanctity of art in an increasingly alienating marketplace, its message still resonates today. But, as an object, it was not built to last.

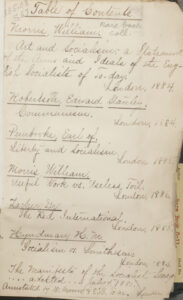

It’s no small irony that Morris’ book on the durability of art has seen much better days. Indeed it’s only relatively rarely that political pamphlets from this era – printed in large batches with cheap materials – still exist. MIT’s copy, though torn, sun-bleached, and slightly stained, nonetheless bears signs of Morris’ influence: resilient paper, intricate illustrations, floral headpieces, and page layout and typography in a familiar medieval style. It is curiously bound together with a large collection of works by contemporaneous communist, socialist, and anarchist British authors – including H.M. Hyndman and Charles Bradlaugh – and several other works by Morris, including the Socialist League’s manifesto.  All are in similar or worse condition than Art and Socialism, and none have the same attention to design.

All are in similar or worse condition than Art and Socialism, and none have the same attention to design.

The condition of this pamphlet is not a contradiction but, rather, living proof of Morris’ dedication to his cause. A consummate idealist devoted to handcraft over machines, Morris knew that it often took sacrifice to improve the common good. In this case, it took cheap, mass-produced pamphlets to disseminate the virtues of permanence, a message that indeed remains venerable amidst physical decay.