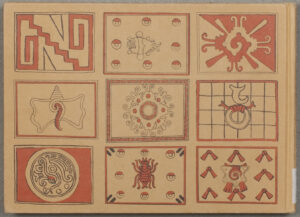

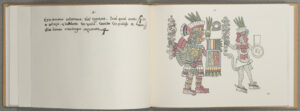

It’s no secret that some of the conquistadors who invaded Mexico in the 16th century were bent on the wholesale destruction of its native culture. Still, there were others – mostly priests – who sought to preserve the Aztec culture (albeit in order to use that knowledge to convert the natives from their pagan ways). Among the priests’ methods was the copying and creation of Aztec manuscripts. “These newly created manuscripts,” Elizabeth Hill Boone tells us, “were generally painted on European paper by Indian artists  whose work reflects the indigenous style of pictorial representation.”

whose work reflects the indigenous style of pictorial representation.”

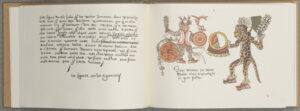

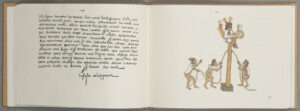

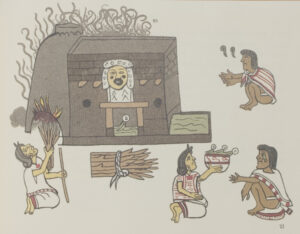

Such is the case with the Codex Magliabechiano. “Sometime between 1529 and 1553,” Boone continues, “a mendicant friar proselytizing among the Indians in Central Mexico requested a native artist (or perhaps several) to paint for him images showing the native deities, calendars, and customs.” When the artist had finished, the friar wrote his descriptions of these rituals on the pages opposite their respective depictions. The result is a near encyclopedia of the Aztec religion.

The manuscript eventually made its way to  Europe, as did so many of the manuscripts created during the conquest. Scholars know that the book was in the collection of Antonio da Marco Magliabechi – for whom it is named – upon his death in 1714, but its earlier provenance is unclear. After Magliabechi’s death, his collection was bequeathed to the city of Florence and later helped form the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, where it now resides.

Europe, as did so many of the manuscripts created during the conquest. Scholars know that the book was in the collection of Antonio da Marco Magliabechi – for whom it is named – upon his death in 1714, but its earlier provenance is unclear. After Magliabechi’s death, his collection was bequeathed to the city of Florence and later helped form the Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale, where it now resides.