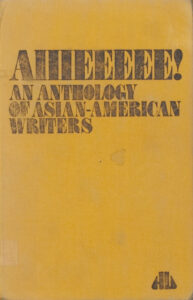

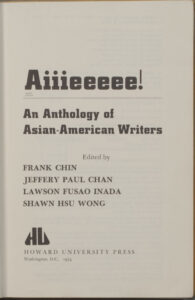

Published: Washington, D.C., 1974

In 1973, there was no such thing as “Asian American literature.” It was not a category discussed by scholars, much less a genre known by writers, booksellers, and the reading public. Then came Aiiieeeee!, published by the Howard University Press in 1974. The title, a reappropriation of the stereotypical scream of “the yellow man” depicted in popular “white American culture,” was meant to represent the cry of “Asian America, so long ignored and forcibly excluded from participation in American culture.”

The editors were four young writers and intellectuals who decided to reclaim the work of fellow Asian American writers forgotten or neglected by critics over the previous fifty years, and to proclaim in their audacious (even defiant) preface and introduction a definition of “Asian American literature.” Their book became a seminal work in Asian American studies and the Asian American political movement, and many scholars today would argue that the collection, featuring writers such as Carlos Bulosan, John Okada, and Louis Chu, established the Asian American literary canon.

When Aiiieeeee! was published, the U.S. was of course embroiled in the Vietnam War, the latest of a string of brutal wars in Asia (going back to the Philippine-American War at the turn of the 20th century) that dehumanized the enemy as a racial “Other.” Asians in America had, over the decades, faced a series of racist assumptions and portrayals: the coolie; the yellow peril; the perpetual foreigner; the exotic Oriental; [insert your favorite racial slur here].

In 1974, the U.S. was also in the middle of social transformation by a series of political movements inspired by the African American civil rights movement and second-wave feminism. The “Yellow Power” movement was one of these, and Aiiieeeee! clearly emerged from that context. Like other activists at the time, the anthology’s editors took a strong position to contest an oppressive social, cultural, and political framework, and their position was and remains controversial.

Answering the problem of the conflation of Asians and Asian Americans – and the assumption that “Asian” and “American” were immutably distinct – they argued that “real” Asian American literature could only emerge from the “American born and raised, who got their China and Japan from the radio, off the silver screen, from television, out of comic books.” Responding to the cultural emasculation of Asian American men, they resisted the feminine. They dismissed many popular Asian American authors as catering to a racist white audience. In addition, the anthology is limited to authors of Chinese, Filipino, and Japanese descent. Despite its limitations, Aiiieeeee! was a defining work for Asian American literature, and the arguments set forth by its editors framed the terms of discussion for decades to come.