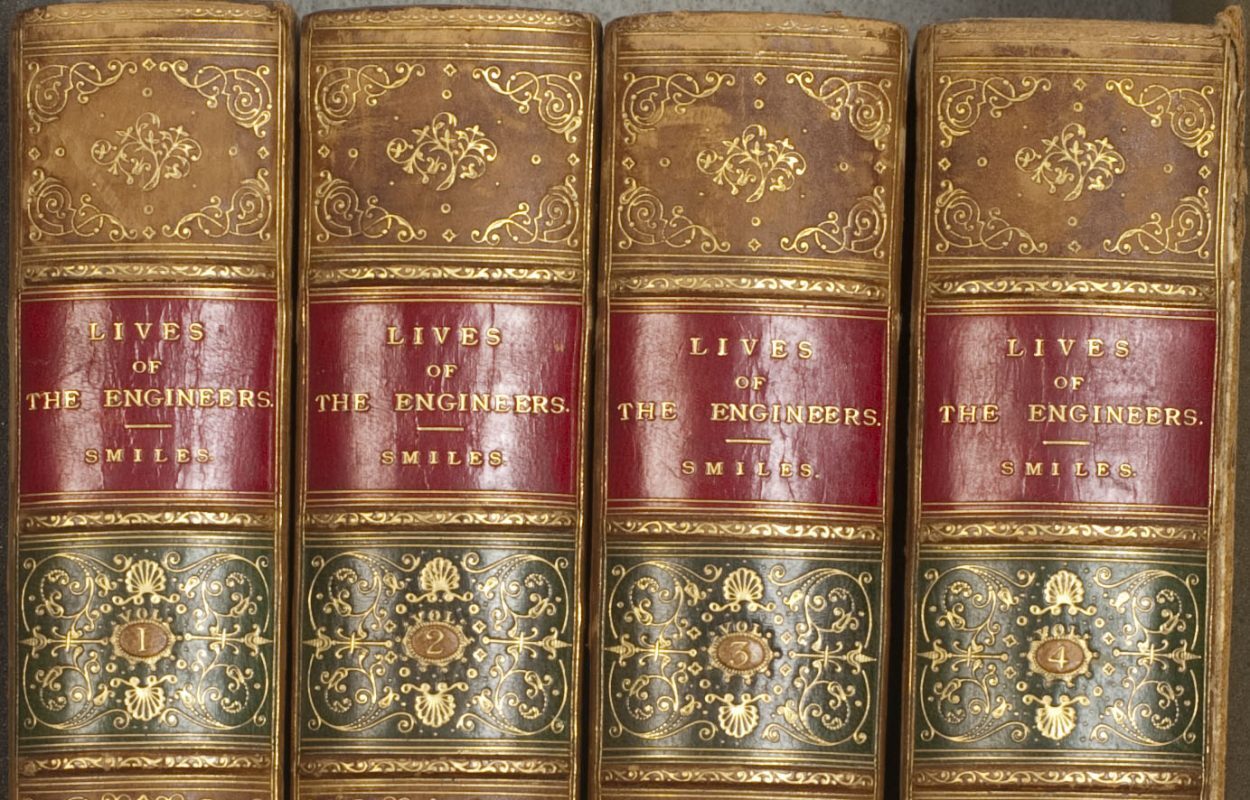

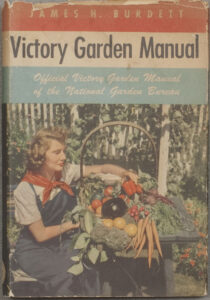

Like our entry for 1942, the title of our 1943 entry begins with the word “victory.” But this is victory of a different and more easily-achievable sort. Instead of triumphing through the use of air power and military might, James H. Burdett’s Victory Garden Manual encourages readers to “be patriotic and plant a Victory Garden!”

In 1920, Burdett had founded the non-profit National Garden Bureau. He was working as an advertising manager for a seed company when he introduced the idea of a central communications office to represent the seed and garden industry. The NGB still exists today, and represents over 50 seed and garden companies.

Victory gardens had become popular and widespread a generation earlier, during World War I, as a means of easing the demand on commercial food production. The victory garden campaign was revived during World War II, when Americans were “summoned as a patriotic duty to grow our own Victory Gardens so as to release commercial crops and canned goods for war demands.” Burdett and the NGB were happy to encourage the patriotic satisfaction, to say nothing of the improved nutrition, that could be attained through the widespread cultivation of private gardens.

Victory gardens had become popular and widespread a generation earlier, during World War I, as a means of easing the demand on commercial food production. The victory garden campaign was revived during World War II, when Americans were “summoned as a patriotic duty to grow our own Victory Gardens so as to release commercial crops and canned goods for war demands.” Burdett and the NGB were happy to encourage the patriotic satisfaction, to say nothing of the improved nutrition, that could be attained through the widespread cultivation of private gardens.

The victory garden campaign of the 1940s was hugely successful, and the efforts of Burdett and the NGB paid out  in addition to paying off: in 1942, seed package sales rose 300% in the United States. According to a 1981 Landscape article by Thomas J. Bassett, in 1944 a full 40% of the fresh vegetables consumed in the United States were grown in victory gardens.

in addition to paying off: in 1942, seed package sales rose 300% in the United States. According to a 1981 Landscape article by Thomas J. Bassett, in 1944 a full 40% of the fresh vegetables consumed in the United States were grown in victory gardens.

After the war ended, interest waned, and gardening as a hobby was abandoned by many who had worked so hard at it while the war was underway. But one of Boston’s original victory gardens is still in operation: founded in 1942, the Richard D. Parker Memorial Victory Garden, located in The Fenway, is the oldest continuously-operating victory garden in the country, and a Boston Historic Landmark.