Hugh Lofting’s Doctor Dolittle series was a consistent best-seller from the time of its initial publication through the mid-20th century. In the rankings of children’s literature, its popularity was for many years topped only by Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland. Though its iconic status had solidified, Doctor Dolittle faded slowly from the cultural radar, enough so that today most people have little knowledge of the original story. (The Eddie Murphy film version from a decade ago has little in common with the book.)

For those unfamiliar with the book, here’s a quick primer (sorry, spoiler alert): English physician learns how to communicate with animals, becomes a veterinarian, sails to Africa to cure a monkey epidemic, gets arrested, escapes, vaccinates monkeys, bleaches the skin of an African prince, encounters pirates, survives, sails home, travels in the circus.

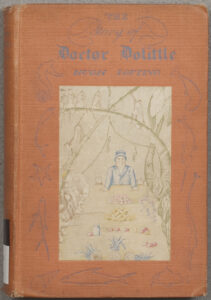

If the part about skin bleaching caught your attention, you are not alone. The original edition of the first book in the series, shown here, includes what are now recognized as racist plot elements, along with the presupposition of European racial superiority that was still common in Britain at the time it was written.

The book clearly denounces slavery and condemns the European exploitation of Africa. But certain plot points – such as the African prince Bumpo who wants to change his appearance in order to attract Sleeping Beauty – remain firmly “of the colonial age.” (To be clear, the Doctor obliges Bumpo’s request only after much consternation.)

This distanced Doctor Dolittle from audiences in the 1960s and 70s. Editions began appearing in edited form, with derogatory language and plot elements revised or removed entirely. In 1986, an edition of the book marking the late author’s 100th birthday was  published after being significantly expurgated at the behest of the author’s son, Christopher Lofting.

published after being significantly expurgated at the behest of the author’s son, Christopher Lofting.

After careful consideration, Lofting concluded that if his father had known that his work would be offensive to anyone, he would have been “the first to make the changes himself.” He continued: “In any case, the alterations are minor enough not to interfere with the style and spirit of the original.” Censored editions of the books are still published today, while the original versions are now widely available through digital sources.

So how did Doctor Dolittle end up in MIT’s collection, anyway? Lofting actually attended the Institute during the first decade of the 20th century, studying civil engineering in case his writing career didn’t pan out. MIT acquired the book in 1948, probably to acknowledge Lofting, who had died the year before.