How does one start as a medical doctor and end up the father of cinematography? An obsession with movement, that’s how. Trained in the 1850s in the emerging field of physiology, Etienne-Jules Marey’s ambition to graphically represent movement resulted in a host of advancements ranging from establishing a link between heart rate and blood pressure to inventing the first portable motion picture camera.

While completing his dissertation on blood circulation, Marey was unsatisfied with the instruments he had to record measurements, so he invented — and manufactured — his own. The first was a “pulse writer,” a device that visually recorded the human pulse. This started a trend that continued throughout his career: get an idea, refine it, build the instruments that bring it to life. Even the laboratory he worked in was his own invention. Using the royalties he accrued from the pulse writer, he took over a flat in Paris that once belonged to the playwright Molière and turned it into a veritable beehive of scientific research. And inside the beehive, the work flowed.

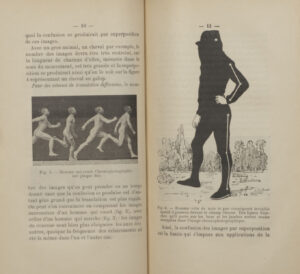

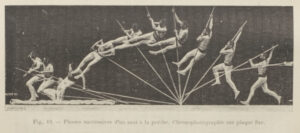

Marey always stayed true to his belief that undertaking the widest breadth of study best expedites the development of science. That’s not to say he championed quantity over quality: his perfectionism was legendary, as were the scathingly sarcastic remarks he directed at less-than-perfect colleagues and students. His study of blood circulation, respiration, and muscle contraction led to an interest in locomotion, first in insects, then birds, then other animals, and finally humans. To better analyze the details of this movement, he developed chronophotography: the recording of several phases of movement onto one photographic surface. Simply put, he invented the photography of movement.

By 1892, Marey’s reputation preceded him, and MIT purchased La photographie du movement hot off the press. It marks the point at which his studies of animal and human movement appear to modern viewers like the actual basis for the hard science of motion pictures. Just as Marey was dedicated to making his inventions as simple and technically accurate as possible, for easy deployment in a clinical setting (he did need to make money, you know), each of his books is an expansion and refinement of the one that preceded it. La Photographie is not his first book on photography or motion pictures, but it is Marey at his refined and pithy best.

By 1892, Marey’s reputation preceded him, and MIT purchased La photographie du movement hot off the press. It marks the point at which his studies of animal and human movement appear to modern viewers like the actual basis for the hard science of motion pictures. Just as Marey was dedicated to making his inventions as simple and technically accurate as possible, for easy deployment in a clinical setting (he did need to make money, you know), each of his books is an expansion and refinement of the one that preceded it. La Photographie is not his first book on photography or motion pictures, but it is Marey at his refined and pithy best.

Marey’s cross-disciplinary, hands-on approach is quintessentially MIT in spirit. Rarely deviating from the study of movement, he circumvented the boundaries of codified academic fields and charted his own territory. His legacy is particularly instructive, so all wannabe innovators take heed: get obsessed, stay obsessed, and don’t be afraid to get your hands dirty.