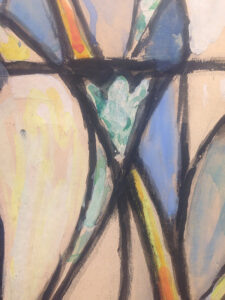

Join the Program on Information Science for a brown bag talk, Can Computers be Feminist? Procedural Politics and Computational Creativity. Discussant Gillian Smith will examine how computers are increasingly taking on the role of a creator — making content for games, participating on Twitter, and generating paintings and sculptures. These computationally creative systems embody formal models of both the product they are creating and the process they follow. Like that of their human counterparts, the work of algorithmic artists is open to criticism and interpretation, but such analysis requires a framework for discussing the politics embedded in procedural systems. In this talk, we will examine the politics that are (typically implicitly) represented in computational models for creativity, and discuss the possibility for incorporating feminist perspectives into their underlying algorithmic design.

Join the Program on Information Science for a brown bag talk, Can Computers be Feminist? Procedural Politics and Computational Creativity. Discussant Gillian Smith will examine how computers are increasingly taking on the role of a creator — making content for games, participating on Twitter, and generating paintings and sculptures. These computationally creative systems embody formal models of both the product they are creating and the process they follow. Like that of their human counterparts, the work of algorithmic artists is open to criticism and interpretation, but such analysis requires a framework for discussing the politics embedded in procedural systems. In this talk, we will examine the politics that are (typically implicitly) represented in computational models for creativity, and discuss the possibility for incorporating feminist perspectives into their underlying algorithmic design.

Gillian Smith is an Assistant Professor in Art+Design and Computer Science at Northeastern University, where she performs research and teaches in the game design program. Her research interests are in computational creativity, computational craft, and gender in games and technology.

Event details

Location: E25-401

Lunch is provided. Please bring your own beverage.

More information

Information Science Brown Bag talks, hosted by the Program on Information Science, consists of regular discussions and brainstorming sessions on all aspects of information science and uses of information science and technology to assess and solve institutional, social and research problems. These are informal talks. Discussions are often inspired by real-world problems being faced by the lead discussant.