Locked letters from the 17th century have been brought to life in videos, and as reconstructed replicas, as part of the exhibition Courtly Rivals in the Hague: Elizabeth Stuart and Amalia von Solms in the Historical Museum of The Hague. MIT Libraries’ conservator, Jana Dambrogio was consulted on the exhibit for her expertise in the art and science of letterlocking.

Locked letters from the 17th century have been brought to life in videos, and as reconstructed replicas, as part of the exhibition Courtly Rivals in the Hague: Elizabeth Stuart and Amalia von Solms in the Historical Museum of The Hague. MIT Libraries’ conservator, Jana Dambrogio was consulted on the exhibit for her expertise in the art and science of letterlocking.

Working with MIT colleagues, Brian Chan, from the MIT Hobby Shop, Artist in Residence Martin Demaine, producer Joe McMaster with Academic Media Production Services, and Ayako Letizia, Curation and Preservation Services conservation assistant, Dambrogio filmed six videos – four demonstrate how letters were folded and secured shut to be “locked” as a form of secure correspondence in the 17th century, while two others demonstrate how ink and coded messages were used. Watch the videos.

“We are fortunate and thankful to have at MIT two paper-folding experts who collaborated with us on this project,” Dambrogio said. Chan portrays secretary Constantijn Huygens in the video that recreates the tiniest spy letter known to exist. Demaine, as Secretary Sir Francis Nethersole, scribes a letter for Queen Elizabeth to sign using a complicated built-in paper lock to secure the letter shut.

“We hope the videos help to show how these writing and security technologies once functioned in the past, and how they connect to a larger information security tradition spanning 10,000 years in cultures throughout the world,” she said.

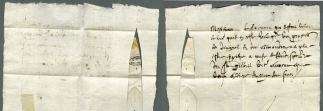

The exhibition, Courtly Rivals, based on Dr. Nadine Akkerman’s publication by the same name, explores the tense relationship between two of the most influential women in the Dutch Republic during the 17th century – Elizabeth Stuart, sometime Queen of Bohemia and her former lady-in-waiting Amalia von Solms, who became Princess of Orange in 1625. Both vividly asserted their courtly and political identity by writing letters. Elizabeth’s corpus of over 2,000 letters shows she was an astute politician, with a vast network of kings, queens, generals, ministers, church leaders, courtiers, and spies. Amalia’s correspondence has just come to light, but it appears she was no different. Both ladies, their secretaries, and their correspondents resorted to intricate methods to lock their letters shut.

One hundred replica locked letters made at MIT were given to attendees at the Hague’s première of the exhibition. The videos and the replicas made by Dambrogio will be featured along side original letters in the exhibition.